As we progress into several years of Covid, post-covid syndromes or “long Covid” * has become a topic of discussion and focus among the scientific/medical community. The CDC has a good general write up I will use below for those not familiar:

- Post-COVID conditions can include a wide range of ongoing health problems; these conditions can last weeks, months, or years.

- Post-COVID conditions are found more often in people who had severe COVID-19 illness, but anyone who has been infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 can experience post-COVID conditions, even people who had mild illness or no symptoms from COVID-19.

- People who are not vaccinated against COVID-19 and become infected may also be at higher risk of developing post-COVID conditions compared to people who were vaccinated and had breakthrough infections.

- While most people with post-COVID conditions have evidence of infection or COVID-19 illness, in some cases, a person with post-COVID conditions may not have tested positive for the virus or known they were infected.

Anecdotally, I have communicated with a number of people and medical professionals dealing with long covid, and I believe it to be a legit condition. What’s most unsettling is that both studies and “real world” experience suggests that even those who had mild cases of covid, can experience some level of long covid symptoms. One study for example – “Mild respiratory COVID can cause multi-lineage neural cell and myelin dysregulation” – suggesting neural damage even with mild covid concluded:

“…even mild COVID could result in a detrimental neuroinflammatory response, including reactivity of these exquisitely sensitive white matter microglia. Given this context, we hypothesized that the inflammatory response to even mild COVID may induce elevation in neurotoxic cytokines/chemokines…”

Another study just published – Neurological and psychiatric risk trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies including 1 284 437 patients – found some very disturbing results; significantly elevated risk of neurological and psychiatric disorders 2 years after people had Covid, even those who had mild Covid! This was a huge study involving 1.2 million people. Below is the abstract and link to the full paper for those who want to read the details of that study (1). As expected, some populations were at higher risk compared to others. A recent National Geographic article covers the potential long term negative impact on the brain even in those who had a mild infection worth a read, such as how shrinkage of the brain may occur:

“Some of the most compelling evidence of neurological damage after mild COVID-19 comes from U.K. researchers who investigated brain changes in people before and after they got the disease.

The 785 participants, between 51 and 81 years old, who had already been scanned before the start of the pandemic, were scanned on average three years apart as part of the U.K. Biobank project. Tests or medical records showed that 401 of these volunteers had become infected with SARS-CoV-2. Most had mild infections; only 15 of the 401 were hospitalised.

The results showed that four and half months after a mild COVID infection, patients had lost, on average, between 0.2 and 2 percent of brain volume and had thinner grey matter than healthy people. By comparison, older adults lose between 0.2 and 0.3 percent of their grey matter each year in the hippocampus, a region linked to memory.”

What Causes Long Covid And How To Treat/Manage It?

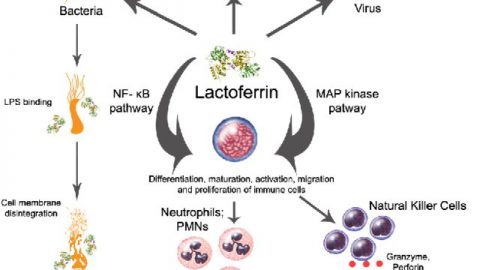

What causes long covid? The exact causes/mechanisms are not yet fully elucidated, I strongly suspect the denominator there is ongoing neuro-inflammation, the pathophysiology driven primarily by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) formation and damage caused there in during the acute infection phase. There appears to be ongoing mitochondrial dysfunction – that continue to “leak” excess ROS – and a primary focus on addressing that aspect specifically will likely improve the situation: Supplements and drugs that support/target glutathione (GSH) production, support of cellular energetics, and mitochondrial function/health, are key aspects in my view.

If that sounds familiar to readers here, it’s due to what I covered at length as to what the data strongly suggests responsible for the serious complications, deaths, and likely, long covid, which I covered in great depth HERE. Unfortunately, that information continues to be overlooked – some may even say actively ignored if they were so inclined – by the medical community writ large. In my view, addressing the model in my main article on covid should be standard of care (SOC) and would reduce serious complications, hospitalizations, and save lives, but I digress… If you or someone you know is dealing with long covid, I’d highly recommend reading that article and applying the information there.

I do not as yet have a specific long covid protocol but do cover the topic in-depth in the article as to specific recs , and creatine may be of value in long covid also, but more data is needed. I would also consider finding a qualified medical professional and consider multiple sessions of IV’s containing those compounds discussed.

That’s what I have been advising those suffering post covid syndromes. Subjective feedback for improvement has been very positive.

(1) Neurological and psychiatric risk trajectories after SARS-CoV-2 infection: an analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies including 1 284 437 patients. The Lancet Psychiatry, Available online 17 August 2022,

Summary

Background

COVID-19 is associated with increased risks of neurological and psychiatric sequelae in the weeks and months thereafter. How long these risks remain, whether they affect children and adults similarly, and whether SARS-CoV-2 variants differ in their risk profiles remains unclear.

Methods

In this analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies, we extracted data from the TriNetX electronic health records network, an international network of de-identified data from health-care records of approximately 89 million patients collected from hospital, primary care, and specialist providers (mostly from the USA, but also from Australia, the UK, Spain, Bulgaria, India, Malaysia, and Taiwan). A cohort of patients of any age with COVID-19 diagnosed between Jan 20, 2020, and April 13, 2022, was identified and propensity-score matched (1:1) to a contemporaneous cohort of patients with any other respiratory infection. Matching was done on the basis of demographic factors, risk factors for COVID-19 and severe COVID-19 illness, and vaccination status. Analyses were stratified by age group (age <18 years [children], 18–64 years [adults], and ≥65 years [older adults]) and date of diagnosis. We assessed the risks of 14 neurological and psychiatric diagnoses after SARS-CoV-2 infection and compared these risks with the matched comparator cohort. The 2-year risk trajectories were represented by time-varying hazard ratios (HRs) and summarised using the 6-month constant HRs (representing the risks in the earlier phase of follow-up, which have not yet been well characterised in children), the risk horizon for each outcome (ie, the time at which the HR returns to 1), and the time to equal incidence in the two cohorts. We also estimated how many people died after a neurological or psychiatric diagnosis during follow-up in each age group. Finally, we compared matched cohorts of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 directly before and after the emergence of the alpha (B.1.1.7), delta (B.1.617.2), and omicron (B.1.1.529) variants.

Findings

We identified 1 487 712 patients with a recorded diagnosis of COVID-19 during the study period, of whom 1 284 437 (185 748 children, 856 588 adults, and 242 101 older adults; overall mean age 42·5 years [SD 21·9]; 741 806 [57·8%] were female and 542 192 [42·2%] were male) were adequately matched with an equal number of patients with another respiratory infection. The risk trajectories of outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection in the whole cohort differed substantially. While most outcomes had HRs significantly greater than 1 after 6 months (with the exception of encephalitis; Guillain-Barré syndrome; nerve, nerve root, and plexus disorder; and parkinsonism), their risk horizons and time to equal incidence varied greatly. Risks of the common psychiatric disorders returned to baseline after 1–2 months (mood disorders at 43 days, anxiety disorders at 58 days) and subsequently reached an equal overall incidence to the matched comparison group (mood disorders at 457 days, anxiety disorders at 417 days). By contrast, risks of cognitive deficit (known as brain fog), dementia, psychotic disorders, and epilepsy or seizures were still increased at the end of the 2-year follow-up period. Post-COVID-19 risk trajectories differed in children compared with adults: in the 6 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection, children were not at an increased risk of mood (HR 1·02 [95% CI 0·94–1·10) or anxiety (1·00 [0·94–1·06]) disorders, but did have an increased risk of cognitive deficit, insomnia, intracranial haemorrhage, ischaemic stroke, nerve, nerve root, and plexus disorders, psychotic disorders, and epilepsy or seizures (HRs ranging from 1·20 [1·09–1·33] to 2·16 [1·46–3·19]). Unlike adults, cognitive deficit in children had a finite risk horizon (75 days) and a finite time to equal incidence (491 days). A sizeable proportion of older adults who received a neurological or psychiatric diagnosis, in either cohort, subsequently died, especially those diagnosed with dementia or epilepsy or seizures. Risk profiles were similar just before versus just after the emergence of the alpha variant (n=47 675 in each cohort). Just after (vs just before) the emergence of the delta variant (n=44 835 in each cohort), increased risks of ischaemic stroke, epilepsy or seizures, cognitive deficit, insomnia, and anxiety disorders were observed, compounded by an increased death rate. With omicron (n=39 845 in each cohort), there was a lower death rate than just before emergence of the variant, but the risks of neurological and psychiatric outcomes remained similar.

Interpretation

This analysis of 2-year retrospective cohort studies of individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 showed that the increased incidence of mood and anxiety disorders was transient, with no overall excess of these diagnoses compared with other respiratory infections. In contrast, the increased risk of psychotic disorder, cognitive deficit, dementia, and epilepsy or seizures persisted throughout. The differing trajectories suggest a different pathogenesis for these outcomes. Children have a more benign overall profile of psychiatric risk than do adults and older adults, but their sustained higher risk of some diagnoses is of concern. The fact that neurological and psychiatric outcomes were similar during the delta and omicron waves indicates that the burden on the health-care system might continue even with variants that are less severe in other respects. Our findings are relevant to understanding individual-level and population-level risks of neurological and psychiatric disorders after SARS-CoV-2 infection and can help inform our responses to them.

(*) = Common terms for the same condition: long COVID, long-haul COVID, post-acute COVID-19, post-acute sequelae of SARS CoV-2 infection (PASC), long-term effects of COVID, and chronic COVID.

Will Brink is the owner of the Brinkzone Blog. Will has over 30 years experience as a respected author, columnist and consultant, to the supplement, fitness, bodybuilding, and weight loss industry and has been extensively published. Will graduated from Harvard University with a concentration in the natural sciences, and is a consultant to major supplement, dairy, and pharmaceutical companies.

His often ground breaking articles can be found in publications such as Lets Live, Muscle Media 2000, MuscleMag International, The Life Extension Magazine, Muscle n Fitness, Inside Karate, Exercise For Men Only, Body International, Power, Oxygen, Penthouse, Women’s World and The Townsend Letter For Doctors.

He’s also been published in peer reviewed journals.

Will is the author of the popular e-books, both accompanied by private members forum access , Bodybuilding Revealed & Fat Loss Revealed.

You can also buy Will’s other books on Amazon, Apple iBook, and Barnes and Noble.

I’m surprised there’s still a debate surrounding long-COVID being an actual medical condition. It’s been thoroughly documented and affected millions of folks, as your article points out. I know the medical community has had a long history of gas lighting, but with this affecting so many people, it seems the vast majority of medical professionals understand this is a legit thing.

I had very minor symptoms indicative of COVID in

late March, 2020, and I still experience bouts of malaise, problematic breathing, and dizziness to this day. One of the symptoms I’ve experienced is POTS, where there’s a circulation issue and blood pools in my extremities, resulting in light headedness, high blood pressure, and heart palpitations when I stand up after sitting or laying down. Thankfully my long COVID is not nearly as bad as some others out there, who are basically bed-ridden.

So yeah, avoid getting COVID and get vaccinated if you haven’t already. Otherwise, you have about a 1 in 20 chance of developing long COVID if you contract the virus.

Covid is so contentious and politicized and such, there seems be nothing people will not debate, including some with the sci/med background to know better. I know people who still can’t smell or taste anything a year later, and there’s even some that will tell you “it’s just a cold” and so forth. Meanwhile, healthy active guy under 50, Bill Phillips, spent over 40 days in a coma and almost died. His brother Shawn was also quite sick, and suffers some bad long covid effects. For some, sure, minimal effects of a mild to bad cold, others, no so much…

Vaccinated or not. I have had 3 boosted friends in there 50s with heart attacks? Does anyone acknowledge this? Also vaccinated are getting break through cases more. Now the CDC is finally saying this.