Written by Monica Mollica

Everybody wants to stay young and vital throughout life. But aging is topic surrounded by many questions and myths; here we’ll get to the bottom of it.

Different types of Aging – Chronological Aging and Physiological Aging

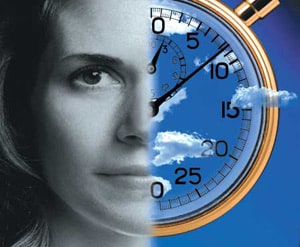

Before we get started, I want to make a distinction of two types of aging; chronological and physiological (or biological).

Chronological age is based on time and is the same for everyone who is born on the same date. It refers to age in number of years.

Physiological age, also called biological age, is the result of many factors, many of which are under your control, and varies from person to person (even if they were born on the same date). It refers to age in terms of physical capacity.

Chronological aging refers to how long you have been alive, and is determined by a mathematical formula that is the same for everybody: current date minus date of birth. It is a function of time and cannot be slowed, stopped or accelerated (a side note: according to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, chronological can be modified, since as one approaches the speed of light, time slows down, and thus so does chronological age. But this isn’t relevant for us earthbound folks).

Physiological aging, on the other hand, describes the state of your body. What’s interesting with physiological aging is that many of the factors that impact it are under your full control (e.g. exercise, nutrition, sleep etc). While chronological and physiological aging are related, the years of your life doesn’t necessarily have much to do with the years of your body. Many people don’t like to tell their (chronological) age; however, if you have taken care of yourself you should be proud of it!

Thus, chronological age and physiologic age do not always coincide, and physical appearance and health status often do not always correspond to what is typical at a particular chronological age. When talking about aging and anti-aging, it is the physiological age we’re referring to. Ok, now that we got that cleared out, let’s move on.

Primary and Secondary Aging

Aging can also be conceptualized as the result of two interactive and overlapping processes, known as primary and secondary aging 1. However, this theory is not universally accepted because it is hard to completely separate each factor.

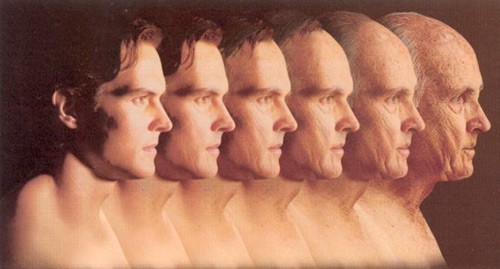

Primary aging, or “intrinsic senescence,” is the progressive deterioration in physical structure and biological function that occurs with advancing age alone, independent of other factors. For example, changes in body composition (ie, decreased bone mineral density, decreased muscle mass, and abdominal fat accumulation) 2-4 and progressive decline of cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and immune function occur normally with increasing age 5-7.

Secondary aging is the accelerated deterioration in organ structure and function that is mediated by diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, or by harmful environmental and lifestyle factors, such as tobacco smoking or excessive sun exposure 8-10.

Definition of Aging

All humans and animals (and other living organisms as well for that matter) undergo changes with time. As a multidimensional reality of life, aging is difficult to define simply. The National Institute on Aging states that “in its broadest sense, aging merely refers to changes that occur during the lifespan”. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines aging as a “process of progressive change in the biological, psychological and social structure of individuals’.  Yet another definition is “the lifelong process of growing older at cellular, organ, and whole-body level throughout the life span” 11.

Yet another definition is “the lifelong process of growing older at cellular, organ, and whole-body level throughout the life span” 11.

From a biological standpoint, aging is often used synonymously with the term senescence, defined as “a biological process of dysfunctional change by which organisms become less capable of maintaining physiological function and homeostasis 12.

Thus, aging can be viewed as a decline, change or development. A decline in body and mental functions has a negative connotation. A change in body and mental functions is neutral in meaning. However, not all aspects of aging decline with age. Our ability to love and be loved does not diminish; at the beach we might pick up grand-kids instead of sweethearts, but our capacity for joy is undiminished. As we will see below, a third view of aging is that of further development. Like age itself, experience, knowledge and wisdom can only increase with time.

One of the reasons for the lack of a singular definition of aging is that it can be considered in so many different ways, according to social, behavioral, physiological, morphological, cellular and molecular changes and norms. Research has led to a number of theories being proposed that may explain the aging process.

Theories of Aging

I want to make it clear right from the start that the ultimate causes of aging remain unknown. The aging process is complex and multifactorial. However, intense research over the past decades has culminated in several theories of aging 13 14. These theories of aging can be categorized into different levels: evolutionary, molecular, cellular and systemic (whole body). The table below summarizes these theories and gives a brief description of each.

Classification and brief description of main theories of aging

|

|

|

|

Biological Level/Theory |

Description |

|

Evolutionary |

|

|

Mutation accumulation |

Mutations that affect health at older ages are not selected against. |

|

Disposable soma |

Somatic cells are maintained only to ensure continued reproductive success; after reproduction, soma becomes disposable. |

|

Antagonistic pleiotropy |

Genes beneficial at younger age become deleterious at older ages. Pleiotropy refers to a single gene that affects multiple physiological traits. |

|

Molecular |

|

|

Gene regulation |

Aging is caused by changes in the expression of genes regulating both development and aging. |

|

Codon restriction |

Fidelity/accuracy of mRNA translation is impaired due to inability to decode codons in mRNA. |

|

Error catastrophe |

Decline in fidelity of gene expression with aging results in increased fraction of abnormal proteins. |

|

Somatic mutation |

Molecular damage accumulates, primarily to DNA/genetic material. |

|

Dysdifferentiation |

Gradual accumulation of random molecular damage impairs regulation of gene expression. |

|

Cellular |

|

|

Cellular senescence-Telomere theory* |

Phenotypes of aging are caused by an increase in frequency of senescent cells. Senescence may result from telomere loss (replicative senescence) or cell stress (cellular senescence). |

|

Free radical |

Oxidative metabolism produces highly reactive free radicals that subsequently damage lipids, protein and DNA. |

|

Wear-and-tear |

Accumulation of normal injury. |

|

Apoptosis |

Programmed cell death from genetic events or genome crisis. |

|

System |

|

|

Neuroendocrine |

Alterations in neuroendocrine control of homeostasis results in aging-related physiological changes. |

|

Immunologic |

Decline of immune function with aging results in decreased incidence of infectious diseases but increased incidence of autoimmunity. |

|

Rate-of-living |

Assumes a fixed amount of metabolic potential for every living organism (live fast, die young). |

Don’t worry if you don’t understand all the terms in the table; I put it here just as a demonstration and summary of the different aging/anti-aging research domains.

The major theories of aging are all specific of a particular cause of aging, providing useful and important insights for the understanding of physiological changes occurring with aging. While proponents of any specific theory might state that their theory is the “one and only”, it should be noted that there is a lot of overlap between them. Alterations of molecular events with aging may lead to cellular alterations, and these, in turn, contribute to organ and systemic failure with evolutionary implications for reproduction and survival.

Thus, the search for a single cause of aging (such as a single gene or the decline of a single body system) has recently been replaced by the view of aging as an extremely complex, multifactorial process 15. In fact, it is very likely that several processes simultaneously interact and operate at different levels of the functional organization 16. In complex, multicellular organisms like humans and animals, the study of interactions among intrinsic (genetic), extrinsic (environmental), and stochastic (random damage to vital molecules) causes provides a more fruitful global approach conducive to a comprehensive and realistic understanding of the aging process. Therefore, different theories of aging should not be considered as mutually exclusive, but may be complementary of others to explain some or all the features of the normal aging process.

As the different theories of aging show, a great deal of the aging process is understood. In several animal species (rodents, monkeys), experimental interventions show that it is possible to delay the onset of functional decline and pathology, and to prolong the life span by manipulating molecular (e.g., free radical reduction), cellular (e.g., mitochondrial protection), and systemic (e.g., endocrine shifts) mechanisms 17. And recent progress in anti-aging research shows exciting promising applications for therapeutic human interventions 18-22. I will cover this in detail in part two of this article.

Usual “Normal” Aging and Successful Aging

Many people see aging as a ti me of cognitive and physical decline. For the past three decades, the general public and most scientists and have accepted this negative age-stereotype as the norm 23 24. The elderly have been viewed and labeled as, ‘ill and/or disabled’, impotent’, ‘ugly’, ‘mentally declining’, ‘mentally ill’, ‘useless’, ‘isolated’, ‘poor’ and ‘depressed’. This negative stereotyping of and discrimination against people because they are old is known as “ageism” 23.

me of cognitive and physical decline. For the past three decades, the general public and most scientists and have accepted this negative age-stereotype as the norm 23 24. The elderly have been viewed and labeled as, ‘ill and/or disabled’, impotent’, ‘ugly’, ‘mentally declining’, ‘mentally ill’, ‘useless’, ‘isolated’, ‘poor’ and ‘depressed’. This negative stereotyping of and discrimination against people because they are old is known as “ageism” 23.

Studies of human aging in the 1960s to 1980s focused on average “normal” age-related functional losses with aging in organs and systems of the body 25. While it is true that bodily functions degrade as we get old, we have all seen people who look younger and are more capable than their peers. This has even been scientifically documented 26 27. The traditional aging research totally neglected this, despite evidence that there are substantial functional differences of older person within the same age groups. Differences in functionality within age groups were simply attributed to genetic endowment. Although genetic factors contribute to the way we age, and is a field of research on its own 28, our genes still only account for a minor part of how gracefully we age. Twin studies that examined the influence of genes on aging have shown that heritability explains about 20-30% of differences in lifespan, and 22% of differences in functioning 29. Both longevity and functioning appear less heritable than cognitive ability 30. Thus, most of the differences between how gracefully we age stem from non-heritable influences of peoples environment and lifestyle, which are not part of the aging process.

Thankfully, in the 1980s and 1990s the view of aging started to shift and challenged the inevitability of functional impairment and of disease in the elderly 31 32. This new view of aging groups the aging processes into three possible paths 31 32:

- Aging, with disease and disability.

- Usual aging, with the absence of overt pathology, but with the presence of some declines in function.

- Successful (or healthy) aging, with little or no pathology and little or no functional loss.

Such a grouping of aging processes de-emphasizes the view that aging is exclusively characterized by declines in functional competence and health, and re-focuses on the substantial heterogeneity among old persons. It also underscores the existence of positive outcomes (i.e. without disability, disease, or major physiological decline), and highlights the possible avoidance of many, if not all, the diseases and disabilities usually associated with old age.

According to the new perspective on aging, mechanisms of successful aging consist of:

- Persistence of normal function.

- Compensatory responses induced by exercise, good nutrition, and education to restore function.

- Interventions to replace deficient function (as represented by replacement therapies).

- Changing of health outcome by modifying risk profiles.

- Prevention of disease.

- Strengthening of social interactions.

With this new aging perspective, the traditional meaning of life span has been replaced by health span.

Successful Aging – what’s in a name?

While the concept of successful aging is popular among both scientists and the general population, there is no one single agreed upon definition for it. There’s even no agreement on the term to be used, with descriptors ranging from successful aging to healthy aging, productive aging, active life expectancy, healthy years, and aging well 31 33-37.

According to the classic definition 31 32 38, successful aging can be characterized as involving three components:

- Freedom of disease and disability.

- High physical and cognitive functioning

- Social and productive engagement.

Later refinements to the definition have added psychosocial aspects to the definition, such as self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental control, purpose in life, and personal growth 39. It has also been suggested that successful aging is a developmental process that can be achieved at any stage in the life span 39.

Regardless what criteria and what terms we use, we all want to have the capacity to thrive and prosper for as long as we live.

Lifespan, healthy life expectancy and longevity

Let’s take a look at some aging trends and projections.

The average lifespan of humans has increased over the past century, mainly a result of a significant improvement in sanitary conditions, public health reforms and improved personal hygiene, advances in medical knowledge and practices, and living standards 40. The average life expectancy at birth is now approximately 75 years in males, and 80 years in females in the USA (World Health Organization 2003). This can be compared to 48 years at the beginning of the 1900s 40.

In the United States, the population aged 65 and older was 3.1 million (4% of the total population) in 1900, in 1950, this number had increased to 12.2 million (8.1% of the total population), and in 2000 it grew to 35 million (12.4% of the total population) 41. In 2008, 39 million people age 65 and over lived in the United States, accounting for 13 percent of the total population.

In the United States, the population aged 65 and older was 3.1 million (4% of the total population) in 1900, in 1950, this number had increased to 12.2 million (8.1% of the total population), and in 2000 it grew to 35 million (12.4% of the total population) 41. In 2008, 39 million people age 65 and over lived in the United States, accounting for 13 percent of the total population.

The older population grew from 3 million in 1900 to 39 million in 2008. The oldest-old population (those age 85 and over) grew from just over 100,000 in 1900 to 5.7 million in 2008. The baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) will start turning 65 in 2011, and the number of older people will increase dramatically during the 2010–2030 period. The older population in 2030 is projected to be twice as large as their counterparts in 2000, growing from 35 million to 72 million and representing nearly 20 percent of the total U.S. population 41. The oldest-old population is projected to grow rapidly after 2030, when the baby boomers move into this age group. The U.S. Census Bureau projects that the population age 85 and over could grow from 5.7 million in 2008 to 19 million by 2050. Some researchers predict that death rates at older ages will decline more rapidly than is reflected in the U.S. Census Bureau’s projections, which could lead to an even faster growth of this population 42-44.

In 2000, the World Health Organization recognized that quality of life in old age is as important as increased longevity, and introduced the concept of healthy life expectancy (also called HALE), defined as the “average number of years that a person can expect to live in ‘full health’ by taking into account years lived in less than full health due to disease and/or injury” (World Health Organization 2000). A simpler way of saying this is that the healthy life expectancy is the number of years an individual is expected to live without any major debilitating diseases (World Health Organization 2000). The healthy life expectancy is about 67 years for males and 71 years for females (World Health Organization 2000).

The maximum observed lifespan represents the longest-lived member(s) of the population 45. In humans, the oldest individual ever recorded was a woman, who died in 1997 in France at the age of 122 years 46. The oldest recorded man died in 1998 at the age of 115 47. By contrast, the average lifespan (or life expectancy at birth) refers to how long people live on average in a given population 40. The theoretical maximum lifespan, or potential maximum lifespan, is the theoretical highest attainable age 45. Today, we don’t know what age this is, but it has been speculated to be around 125 years 48.

Do we have an immutable life span limit?

A fundamental question in aging research is whether humans possess an immutable life span limit. However, whether the maximum observed lifespan can and has increased is still controversial. According to some scientists, it has remained constant 49 50. In contrast, others have shown that the maximum age at death has been rising over the past century in industrialized countries 51. For ex. statistical analysis of the longest available series of reliable information on the upper limits of achieved human life span, has shown that from 1969 to 1999 maximum life span increased by 1.1 years every decade. The table below shows more specifically the progressive changes in the average and maximum life spans 40.

Average change (in Years Per Decade) in average and maximum life spans in Sweden 51.

|

|

1861–1960 |

1970–1999

|

|

Average life span (life expectancy at birth) |

3.1 |

1.8 |

|

Maximum observed life span (maximum reported age at death) |

0.4 |

1.5 |

Thus, even though the average life span has increased more than the maximum observed life span, the data clearly shows that the maximum observed life span is not immutable, and that our life span limit is steadily increasing as well.

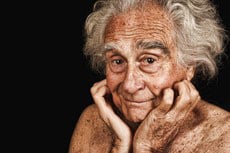

Predictors of Successful Aging – valuable lessons from our current centenarians

Let’s take a look at what our current successful elders are doing to age successfully, and what physiological characteristics they display. Centenarians, those who are 100 years old or older, represent an intriguing model for ageing studies, since they demonstrate extreme longevity, and at the same time a proportion of them have aged successfully and have less diseases than the younger elderly 52 53.

It has been shown that autonomous centenarians partake in regular exercise (in proportion to their physical capabilities), have more frequent intakes of protein and regular sleep patterns, and no history of drinking 54. Other consistent predictors of healthy aging are low blood pressure, low serum glucose, not smoking cigarettes, and not being obese 55. Typical of autonomous centenarians are better visual acuity, preserved masticatory ability and living at home 54. They have been relatively healthy and independent for most of their lives and don’t experience a significant functional decline until the very end of their lives 56.

It has been shown that autonomous centenarians partake in regular exercise (in proportion to their physical capabilities), have more frequent intakes of protein and regular sleep patterns, and no history of drinking 54. Other consistent predictors of healthy aging are low blood pressure, low serum glucose, not smoking cigarettes, and not being obese 55. Typical of autonomous centenarians are better visual acuity, preserved masticatory ability and living at home 54. They have been relatively healthy and independent for most of their lives and don’t experience a significant functional decline until the very end of their lives 56.

Other factors that have been documented in centenarians are a higher resting metabolic rate and lower waist-to-hip ratio 57 58, higher IGF-1 levels 59, and preserved thyroid function 60, immunity 61 insulin sensitivity and glucose action 62. Centenarians also have been shown to have a less atherogenic plasma lipid profile (lower LDL and higher HDL, and larger LDL and HDL particle sizes) than aged subjects 63 64. Also, while the prevalence of dementia increases with age, it is not inevitable in centenarians 65-67, and cognition actually seems to be important for longevity 68.

The rise of Generation C

According to watchers of consumer trends, a new generation – Generation C – will emerge in the course of the next 10 years. Born after 1990, they are referred to as “digital natives”. Now beginning to attend university and enter the workforce, they are expected to transform the world as we know it 69. The “C” stands for “connected,” “communicating,” “content-centric,” “creative,” and “change”; however, it may just as well stand for “centenarian” as for the first time in history many of this birth cohort will live 100 years or more.

Centenarians, once considered rare, are now starting to become commonplace. Indeed, they are the fastest growing demographic group of the world’s population, their numbers having roughly doubled every decade since 1950, and they are globally projected to more than quintuple between 2005 and 2030 70.

Allostatic load – small insults add up over lifetime

Beyond the biological effects of aging, much of the illness and disability in the elderly is related to risk factors present at younger ages 55. If you are in your 30s and think “I start to worry about that when I hit 50” you’re wrong. The sooner you start to take care of your health by exercising regularly and eating healthy, the better off you will be when you get older. Even early age nutrition and exercise habits in kids and teenagers have an impact the aging process 71. It has been shown that healthy lifestyle choices encompassing diet, physical activity, body fat (weight) reduction and stress control can add at least ten years to healthy, good quality, life expectancy 72.

Related to successful aging and the risk for diseases and functional declines is allostatic load, which is the cumulative physiologic toll “wear and tear” exacted on the body over time by efforts to adapt to life experiences and demands 73 74. Allostatic load is measured through a composite index of indicators of cumulative strain on several organs and tissues, but especially on the cardiovascular system, and reflects the damaging consequences of the body’s response to chronic stress 75 76.

Higher allostatic load scores have been associated with increased mortality 73 and poorer cognitive and physical functioning 74, and predict larger decrements in cognitive and physical functioning in older men and women 74. In addition to being an index of wear and tear on the body, elevations in allostatic load predict an increased risk for the incidence of cardiovascular disease, independent of sociodemographic and other health risk factors 74. Allostatic load is also an independent predictor of functional decline in elderly men and women 77.

Thus, even if you’re in your 20s or 30s, it is smart to think about the health implications of your current habits and lifestyle.

It is never too late

If you think after having read the previous paragraph “Shoot, it’s too late for me now, the damage is already done”, you’re wrong! Several studies have shown that improving health related habits and reducing risk factors even at older ages confer substantial benefits.

ages confer substantial benefits.

For example, a study followed middle-aged men (45-68 years) who were free of morbidity and functional impairments at baseline, over to 40 years (1965-2005). The purpose was to assess overall and exceptional survival. Exceptional survival was defined as survival to 75, 80, 85, or 90 years without incidence of 6 major chronic diseases and without physical and cognitive impairment. Of the participants, 42% survived to age 85 years and 11% met the criteria for exceptional survival to age 85 years. High grip strength and avoidance of overweight, hyperglycemia, hypertension, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption were associated with both overall and exceptional survival. In addition, high education and avoidance of hypertriglyceridemia were associated with exceptional survival, and lack of a marital partner was associated with mortality before age 85 years. A statistical risk factor models indicated that the probability of survival to oldest age is as high as 69% with no risk factors and as low as 22% with 6 or more risk factors. The probability of exceptional survival to age 85 years was 55% with no risk factors but decreased to 9% with 6 or more risk factors. Thus, if you have any of the common risk factors that face most middle-age individuals, and make lifestyle changes to correct them, you will increase your probability of a long and healthy life 78.

In another study that evaluated the relationship between changes in physical fitness and risk of mortality in men, it was found that going from being unfit to fit leased to a reduction in mortality risk of 44% relative to those who remained unfit 5 years later, even after adjusting for other risk factors. For each minute increase in maximal treadmill time, there was a corresponding 8% decrease in risk of mortality. This is quite impressive, and shoul d encourage unfit folks to improve their fitness by starting a physical activity program even if they are in the middle-age 79.

d encourage unfit folks to improve their fitness by starting a physical activity program even if they are in the middle-age 79.

In a study of the impact of middle-age physical activity on physical function in early old age, individuals aged 39 to 63 years at baseline, were followed to 9 years. It was found that relatively fit and healthy middle-aged men and women who were physically active at recommended levels, were more likely to report high physical function at follow-up, compared to their sedentary counterparts. The association between initial level of physical activity and high physical function at follow-up remained after adjustment for baseline level of physical function and the presence of long-standing illness. Thus, participation in a physically active lifestyle during mid-life appears to be critical to the maintenance of high physical function in old age 80.

Benefits of risk factor prevention in Americans aged 51 years and older was shown in a study that assessed the potential health and economic impact of reducing common risk factors in older Americans. The gain in life span from successful treatment of obesity, hypertension (high blood pressure) and diabetes was estimated to be up to 4 years. Despite living longer, those successfully treated for any of these risk factors would have lower lifetime medical spending, which indicates that the extra years added to life are healthy disease free years 81.

Even at old age we have a notable capacity to adapt to regular exercise. Aerobic exercise results in improvements in functional capacity and reduced risk of developing type II diabetes in the elderly. High-intensity resistance training (above 60% of the 1 repetition maximum) has been demonstrated to cause large increases in strength in the elderly. In addition, resistance training results in significant increases in muscle size in elderly men and women, and has a positive effect on multiple risk factors for osteoporotic fractures in previously sedentary post-menopausal women. Thus, old age does not decrease the ca pacity to adapt to a progressive resistance training program, and exercise may minimize or reverse the syndrome of physical frailty which is so prevalent among the oldest old 82. Even in very elderly 87 year old people resistance exercise training is a feasible and effective means of counteracting muscle weakness and physical frailty 83.

pacity to adapt to a progressive resistance training program, and exercise may minimize or reverse the syndrome of physical frailty which is so prevalent among the oldest old 82. Even in very elderly 87 year old people resistance exercise training is a feasible and effective means of counteracting muscle weakness and physical frailty 83.

A very interesting study sought to characterize the muscle weakness of the very old and its reversibility through strength training 84. Ten frail, institutionalized volunteers aged 90-96 years undertook 8 weeks of high-intensity resistance training. Strength gains averaged 174% and midthigh muscle area increased 9.0%, while gait speed improved 48% after training. It was concluded that high-resistance weight training leads to significant gains in muscle strength, size, and functional mobility among frail residents of nursing homes up to 96 years of age 84. Thus, with exercise training of sufficient frequency, intensity and duration, it is quite possible to increase muscle mass, strength and endurance at any age, and prevent sarcopenia, obesity, type II diabetes, coronary artery disease, hypertension, and osteoporosis. There is no pharmacological intervention that holds a greater promise of improving health and promoting independence in the elderly than does exercise 85.

These studies clearly prove that it is never too late to start living healthier and benefit from those changes. While it’s certainly better to start healthy habits at a young age and keep them for a lifetime, for those who have strayed (that is, most people!) nature is remarkably forgiving. Not only can we recover much lost function and decrease risk, but we can actually increase function and health beyond our prior level.

The three steps toward extending your life and health span

One way to look at our path to longevity and health span is to regard it as a journey over three sequential steps. Step 1 is based on therapies that exist today, like exercise, nutrition and dietary supplementation. Step 1 will take us to step 2, which consists of biotechnology therapies. Step 2 will then take us to step 3, the nanotechnology/artificial intelligence revolution, which will lead to life spans that are currently incomprehensible, but which will soon be commonplace, measuring in the hundreds of years 86 87.

The step 2 and step 3 anti-aging technologies, which have potential to extend our health span more than we ever dreamed was possible, are controversial topics and surrounded by ethical and political issues. Since BrinkZone is a site about nutrition and exercise, I will not cover these topics here.

Wrap up

There’s no excuse to treat the aging process itself as a reason for disability and disease at older age. A wealth of studies are showing over and over again that many, if not most, of the aging related functional declines and disabilities and can be prevented with non-aging related lifestyle factors like exercise and nutrition. A successful old age lies not so much in out stars and genes, as in ourselves. Step up, take control, and start adding both years to your life, and life to your years!

In part two of this article I will cover nutrition and dietary supplements that are currently being researched for their potential anti-aging effects, and that you can expect to see popping up on the supplement shelves in the near future. Stay tuned!

1. Holloszy JO. The biology of aging. Mayo Clinic proceedings. Mayo Clinic 2000;75 Suppl:S3-8; discussion S8-9.

2. Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston CC, Jr., Lindsay RL, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 1997;12(11):1761-8.

3. Roubenoff R. Sarcopenic obesity: does muscle loss cause fat gain? Lessons from rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2000;904:553-7.

4. Seidell JC, Oosterlee A, Deurenberg P, Hautvast JG, Ruijs JH. Abdominal fat depots measured with computed tomography: effects of degree of obesity, sex, and age. European journal of clinical nutrition 1988;42(9):805-15.

5. Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part II: the aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation 2003;107(2):346-54.

6. Lindeman RD, Tobin J, Shock NW. Longitudinal studies on the rate of decline in renal function with age. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1985;33(4):278-85.

7. Schmidt CD, Dickman ML, Gardner RM, Brough FK. Spirometric standards for healthy elderly men and women. 532 subjects, ages 55 through 94 years. The American review of respiratory disease 1973;108(4):933-9.

8. Kloting N, Bluher M. Extended longevity and insulin signaling in adipose tissue. Experimental gerontology 2005;40(11):878-83.

9. Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S. Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2005;82(5):923-34.

10. Yin L, Morita A, Tsuji T. Skin aging induced by ultraviolet exposure and tobacco smoking: evidence from epidemiological and molecular studies. Photodermatology, photoimmunology & photomedicine 2001;17(4):178-83.

11. Timiras PS. Old Age as a Stage of Life: Common Terms Related to Aging and Methods Used to Study Aging. Physiological Basis of Aging and Geriatrics. 4th ed ed: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc., 2007:407.

12. Crews DE. Human Senescence: Evolutionary and Biocultura Perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

13. Medvedev ZA. An attempt at a rational classification of theories of ageing. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 1990;65(3):375-98.

14. Carey JR, Zou S. Theories of Life Span and Aging. In: Timiras PS, editor. Physiological Basis of Aging and Geriatrics: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc., 2007:55-70.

15. Kowald A, Kirkwood TB. A network theory of ageing: the interactions of defective mitochondria, aberrant proteins, free radicals and scavengers in the ageing process. Mutation research 1996;316(5-6):209-36.

16. Franceschi C, Valensin S, Bonafe M, Paolisso G, Yashin AI, Monti D, et al. The network and the remodeling theories of aging: historical background and new perspectives. Experimental gerontology 2000;35(6-7):879-96.

17. Timiras PS. Physiological Basis of Aging and Geriatrics. 4th ed ed: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc., 2007.

18. Kelly G. A review of the sirtuin system, its clinical implications, and the potential role of dietary activators like resveratrol: part 1. Alternative medicine review : a journal of clinical therapeutic 2010;15(3):245-63.

19. Kelly GS. A review of the sirtuin system, its clinical implications, and the potential role of dietary activators like resveratrol: part 2. Alternative medicine review : a journal of clinical therapeutic 2010;15(4):313-28.

20. Daffner KR. Promoting successful cognitive aging: a comprehensive review. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2010;19(4):1101-22.

21. Imai S. A possibility of nutriceuticals as an anti-aging intervention: activation of sirtuins by promoting mammalian NAD biosynthesis. Pharmacological research : the official journal of the Italian Pharmacological Society 2010;62(1):42-7.

22. Butler RN, Fossel M, Harman SM, Heward CB, Olshansky SJ, Perls TT, et al. Is there an antiaging medicine? The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2002;57(9):B333-8.

23. Butler RN. Age-ism: another form of bigotry. The Gerontologist 1969;9(4):243-6.

24. Lupien SJ, Wan N. Successful ageing: from cell to self. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 2004;359(1449):1413-26.

25. Shock NW. Age changes in physiological functions in the total animal: the role of tissue loss. In: Strehler BL, Ebert JD, Shock NW, editors. The Biology Of Aging: A Symposium. Washington, DC: Am. Inst. Biol. Sci., 1960.

26. Rowe JW. Health care of the elderly. The New England journal of medicine 1985;312(13):827-35.

27. Shock NW, al. E. Normal Human Aging: The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1984.

28. Glatt SJ, Chayavichitsilp P, Depp C, Schork NJ, Jeste DV. Successful aging: from phenotype to genotype. Biological psychiatry 2007;62(4):282-93.

29. Gurland BJ, Page WF, Plassman BL. A twin study of the genetic contribution to age-related functional impairment. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2004;59(8):859-63.

30. Read S, Pedersen NL, Gatz M, Berg S, Vuoksimaa E, Malmberg B, et al. Sex differences after all those years? Heritability of cognitive abilities in old age. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2006;61(3):P137-43.

31. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Human aging: usual and successful. Science 1987;237(4811):143-9.

32. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. Aging (Milano) 1998;10(2):142-4.

33. Butler RN. What is ‘successful’ aging? Geriatrics 1988;43(5):11, 15.

34. Butler RN. The study of productive aging. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2002;57(6):S323.

35. Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: a comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry 2006;14(1):6-20.

36. Peel NM, McClure RJ, Bartlett HP. Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. American journal of preventive medicine 2005;28(3):298-304.

37. Vaillant GE, Mukamal K. Successful aging. The American journal of psychiatry 2001;158(6):839-47.

38. Rowe JW, Kahn RL. Successful aging. The Gerontologist 1997;37(4):433-40.

39. Ryff CD. Successful aging: a developmental approach. The Gerontologist 1982;22(2):209-14.

40. Wilmoth Jr. Human Longevity in Historical Perspective. Physiological Basis of Aging and Geriatrics. 4th ed ed: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc., 2007:11-22.

41. Services DoHaH. Older Americans 2000: key indicators of well-being., 2000.

42. Horiuchi S. Greater lifetime expectations. Nature 2000;405(6788):744-5.

43. Oeppen J, Vaupel JW. Demography. Broken limits to life expectancy. Science 2002;296(5570):1029-31.

44. Tuljapurkar S, Li N, Boe C. A universal pattern of mortality decline in the G7 countries. Nature 2000;405(6788):789-92.

45. Carey JR, Zou S. Theories of Life Span and Aging. In: Timiras PS, editor. Physiological Basis of Aging and Geriatrics. 4th ed ed: Informa Healthcare USA, Inc., 2007:55-68.

46. Robine J-M, Allard M. Jeanne Calment: validation of the duration of her life. In: Jeune B, Vaupel JW, editors. Validation of Exceptional Longevity. Odense, Denmark:: Odense University Press, 1999:145–72.

47. Skytthe A, Jeune B, Wilmoth JR. Age validation of the oldest man In: Jeune B, Vaupel JW, editors. Validation of Exceptional Longevity. Odense, Denmark:: Odense University Press, 1999:173-88.

48. Weon BM, Je JH. Theoretical estimation of maximum human lifespan. Biogerontology 2009;10(1):65-71.

49. Cutler RG. Evolution of human longevity: a critical overview. Mechanisms of ageing and development 1979;9(3-4):337-54.

50. Cutler RG. Evolution of human longevity. Advances in pathobiology 1980;7:43-79.

51. Wilmoth JR, Deegan LJ, Lundstrom H, Horiuchi S. Increase of maximum life-span in Sweden, 1861-1999. Science 2000;289(5488):2366-8.

52. Perls T, Levenson R, Regan M, Puca A. What does it take to live to 100? Mechanisms of ageing and development 2002;123(2-3):231-42.

53. Stathakos D, Pratsinis H, Zachos I, Vlahaki I, Gianakopoulou A, Zianni D, et al. Greek centenarians: assessment of functional health status and life-style characteristics. Experimental gerontology 2005;40(6):512-8.

54. Ozaki A, Uchiyama M, Tagaya H, Ohida T, Ogihara R. The Japanese Centenarian Study: autonomy was associated with health practices as well as physical status. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2007;55(1):95-101.

55. Reed DM, Foley DJ, White LR, Heimovitz H, Burchfiel CM, Masaki K. Predictors of healthy aging in men with high life expectancies. American journal of public health 1998;88(10):1463-8.

56. Hitt R, Young-Xu Y, Silver M, Perls T. Centenarians: the older you get, the healthier you have been. Lancet 1999;354(9179):652.

57. Rizzo MR, Mari D, Barbieri M, Ragno E, Grella R, Provenzano R, et al. Resting metabolic rate and respiratory quotient in human longevity. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2005;90(1):409-13.

58. Srikanthan P, Seeman TE, Karlamangla AS. Waist-hip-ratio as a predictor of all-cause mortality in high-functioning older adults. Annals of epidemiology 2009;19(10):724-31.

59. Paolisso G, Ammendola S, Del Buono A, Gambardella A, Riondino M, Tagliamonte MR, et al. Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and IGF-binding protein-3 in healthy centenarians: relationship with plasma leptin and lipid concentrations, insulin action, and cognitive function. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1997;82(7):2204-9.

60. Mariotti S, Barbesino G, Caturegli P, Bartalena L, Sansoni P, Fagnoni F, et al. Complex alteration of thyroid function in healthy centenarians. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 1993;77(5):1130-4.

61. Franceschi C, Monti D, Sansoni P, Cossarizza A. The immunology of exceptional individuals: the lesson of centenarians. Immunology today 1995;16(1):12-6.

62. Paolisso G, Gambardella A, Ammendola S, D’Amore A, Balbi V, Varricchio M, et al. Glucose tolerance and insulin action in healty centenarians. The American journal of physiology 1996;270(5 Pt 1):E890-4.

63. Paolisso G, Gambardella A, Ammendola S, Tagliamonte MR, Rizzo MR, Capurso A, et al. Preserved antilipolytic insulin action is associated with a less atherogenic plasma lipid profile in healthy centenarians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 1997;45(12):1504-9.

64. Barzilai N, Atzmon G, Schechter C, Schaefer EJ, Cupples AL, Lipton R, et al. Unique lipoprotein phenotype and genotype associated with exceptional longevity. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2003;290(15):2030-40.

65. Andersen-Ranberg K, Vasegaard L, Jeune B. Dementia is not inevitable: a population-based study of Danish centenarians. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2001;56(3):P152-9.

66. Silver M, Newell K, Hyman B, Growdon J, Hedley-Whyte ET, Perls T. Unraveling the mystery of cognitive changes in old age: correlation of neuropsychological evaluation with neuropathological findings in the extreme old. International psychogeriatrics / IPA 1998;10(1):25-41.

67. Silver MH, Jilinskaia E, Perls TT. Cognitive functional status of age-confirmed centenarians in a population-based study. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2001;56(3):P134-40.

68. Hagberg B, Bauer Alfredson B, Poon LW, Homma A. Cognitive functioning in centenarians: a coordinated analysis of results from three countries. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2001;56(3):P141-51.

69. AME Info. The Rise of Generation C, 2010.

70. U.S. National Institute on Aging. Why population aging matters. In: Health NIo, editor. Tech. Rep. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services PHS, 2007.

71. Dwyer J. Starting down the right path: nutrition connections with chronic diseases of later life. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2006;83(2):415S-20S.

72. Fraser GE, Shavlik DJ. Ten years of life: Is it a matter of choice? Archives of internal medicine 2001;161(13):1645-52.

73. Seeman TE, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Singer BH. Allostatic load as a marker of cumulative biological risk: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2001;98(8):4770-5.

74. Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, Horwitz RI, McEwen BS. Price of adaptation–allostatic load and its health consequences. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Archives of internal medicine 1997;157(19):2259-68.

75. McEwen BS. Stressed or stressed out: what is the difference? Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN 2005;30(5):315-8.

76. McEwen BS, Wingfield JC. What is in a name? Integrating homeostasis, allostasis and stress. Hormones and behavior 2010;57(2):105-11.

77. Karlamangla AS, Singer BH, McEwen BS, Rowe JW, Seeman TE. Allostatic load as a predictor of functional decline. MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2002;55(7):696-710.

78. Willcox BJ, He Q, Chen R, Yano K, Masaki KH, Grove JS, et al. Midlife risk factors and healthy survival in men. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2006;296(19):2343-50.

79. Blair SN, Kohl HW, 3rd, Barlow CE, Paffenbarger RS, Jr., Gibbons LW, Macera CA. Changes in physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy and unhealthy men. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1995;273(14):1093-8.

80. Hillsdon MM, Brunner EJ, Guralnik JM, Marmot MG. Prospective study of physical activity and physical function in early old age. American journal of preventive medicine 2005;28(3):245-50.

81. Goldman DP, Zheng Y, Girosi F, Michaud PC, Olshansky SJ, Cutler D, et al. The benefits of risk factor prevention in Americans aged 51 years and older. American journal of public health 2009;99(11):2096-101.

82. Evans WJ. Effects of exercise on body composition and functional capacity of the elderly. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 1995;50 Spec No:147-50.

83. Fiatarone MA, O’Neill EF, Ryan ND, Clements KM, Solares GR, Nelson ME, et al. Exercise training and nutritional supplementation for physical frailty in very elderly people. The New England journal of medicine 1994;330(25):1769-75.

84. Fiatarone MA, Marks EC, Ryan ND, Meredith CN, Lipsitz LA, Evans WJ. High-intensity strength training in nonagenarians. Effects on skeletal muscle. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 1990;263(22):3029-34.

85. Evans WJ, Campbell WW. Sarcopenia and age-related changes in body composition and functional capacity. The Journal of nutrition 1993;123(2 Suppl):465-8.

86. Freitas RA. Nanomedicine: Basic Capabilities. 1st ed: Landes Bioscience, 1999.

87. Tibbals HF. Medical Nanotechnology and Nanomedicine (Perspectives in Nanotechnology). 1st ed: CRC Press, 2010.

About Monica Mollica > www.trainergize.com

Monica Mollica has a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Nutrition from the University of Stockholm, Sweden, and is an ISSA Certified Personal Trainer. She works a dietary consultant, health journalist and writer for www.BrinkZone.com, and is also a web designer and videographer.

Monica Mollica has a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in Nutrition from the University of Stockholm, Sweden, and is an ISSA Certified Personal Trainer. She works a dietary consultant, health journalist and writer for www.BrinkZone.com, and is also a web designer and videographer.

Monica has admired and been fascinated by muscular and sculptured strong athletic bodies since childhood, and discovered bodybuilding as an early teenager. Realizing the importance of nutrition for maximal results in the gym, she went for a major in Nutrition at the University.

During her years at the University she was a regular contributor to the Swedish bodybuilding magazine BODY, and she has published the book (in Swedish) “Functional Foods for Health and Energy Balance”, and authored several book chapters in Swedish publications.

It was her insatiable thirst for knowledge and scientific research in the area of bodybuilding and health that brought her to the US. She has completed one semester at the PhD-program “Exercise, Nutrition and Preventive Health” at Baylor University Texas, at the department of Health Human Performance and Recreation, and worked as an ISSA certified personal trainer. Today, Monica is sharing her solid experience by doing dietary consultations and writing about topics related to bodybuilding, fitness, health and anti-aging.

Very smart and really hot! A very in depth article written by an awesome woman

Thanks for the compliment 🙂

Thanks for the article Monica, very well researched!

I just have to add that one of my personal Mentors that I look up to… Is None other than Mr Clarence Bass himself , An Age defying Wizard of Health and Fitness.. Who has blasted the Myth of Ageing through his own years..

Keep up the good work

Chris

Yes, Mr Bass is a prime example of successful aging; you are lucky to have him as your mentor.

Yes, Mr Bass is a prime example of successful aging 🙂

Awesome!!!!!!!!

Brilliant stuff,

“Because of their low functional status and high incidence of chronic disease, there is no segment of the population that can benefit more from exercise training than the elderly” -82

I’m currently working through NASM PT and on a Math and Nutrition major. I haven’t gotten to the section in the PT textbook on training elderly clients, so I’m stunned by how useful resistance training can be. I assumed that a program emphasizing both stabilization and muscular endurance would be the limit. However, I’m surprised that heavier lifting (>60% LM) would be encouraged. After considering that, the proper foundational training was completed, then gains in hypertrophy and maximal strength could certainly be possible.

On a seperate note, I’m hypothesizing that deconditioning and overall aging is as much a psychological problem as a biological one. In a fascinating book on memory, “Your Memory How It Works & How To Improve It”, Kenneth L. Higbee, PH.D, states that,

“Most researchers do agree that there is probably no single process that accounts for age differences in memory. Some of the aging effects may be due to physiological cause (e.g., cell loss or central nervous system dysfunction), *but many of the effects are probably due to psychological causes or other causes that may be amenable to change*. Examples of such causes suggested by research include motivation, distraction, response speed, motor skills, lazy mental habits, interest, depression, health, education, and anxiety in research setting that are new or involve time pressure. Notice that many of these factors have nothing to do directly with mental ability.” (Higbee, page 10)

Bottom line, the passage of time is something we cannot change. However, how well we age is certainly under our control. This in respect to both physical prowess and mental acuity.

You’re completely right; actually, in the more scientific and detailed discussions on successful aging, several psychological and mental aspects have been added to the criterion and its definition.

Physical activitie, at least for me, has been one of the most important factors on my psychological balance, it can help with depression, self esteem, focus, etc..

So, in my oppinion, fisical exercise itself can be seen as a menta exercise too.

Good one Will,

One of the most interesting facts I learn t about blue zones [areas where people live the longest] is they have a high GSH level.

I didn’t write it….

Yes, GSH (reduced glutathione) is a major endogenous antioxidant (produced by the body). It is used in metabolic and biochemical reactions such as DNA synthesis and repair, protein synthesis, prostaglandin synthesis, amino acid transport, and enzyme activation. Thereby it affects every system in the body.

While glutathione supplementation isn’t effective at increasing blood or intracellular levels, there are other supplements that do, especially NAC (N-acetylcysteine) and SAMe (S-adenosylmethionine). Whey protein and vitamin D also have been shown to increase glutathione levels within cells. Other supplements, that indirectly restore glutathione levels, are ALA (alpha lipoic acid) and silymarin.

Thus, glutathione is a very interesting multi-functional substance in our bodies, which definitely deserves its own article…I get the hint…wink:)

Great article – a detailed, objective article on GSH would be much appreciated. I take NAC and whey with my post W/O drink – do you know if ‘Protect 120 Glutathione’ cream is effective, as it claims to be?

re. Kent’s comments – He seems to assume that everyone his age has had operations and ailments. Not so. At 63, and having also weight trained and eaten properly my whole adult life, I have had no major injuries or illnesses, and feel as fit and strong as I did 20 years ago – surely the point of all that work. So it is good that Monica and Will are aware of aging at a relatively young age – if more fat, unhealthy Americans and Europeans did likewise, the hospitals would not be so full.

Personally, I think an article dedicated to glutathione/GSH would bore the pants of most people, and there are a number of good write ups on the importance of GSH out there. However, an article that focuses on nutrients, drugs, etc that impact GSH, with discussion of the importance of GSH, would be more useful to readers here. If you do a search for Glutathione and or GSH here, you should turn up a number of my articles that are generally focused on the impact of whey on GSH, with some discussion on the importance of GSH in a variety of ways. If Monica wants to write a GSH specific articles, she’s welcome to it 🙂

Yay! 🙂

Yes, of course, that’s what I meant. Problem is, there is a huge amount online on everything; how do you sort the wheat from the chaff? Objective, unbiased, science based info is what I (and I’m sure your other readers) want, which is why I come here…

Excellent article, very thorough. Might I suggest a summary at the top for those of us short on time?

Yes, I know I’m guilty of writing loooong articles, lol. Next time I go over the word limit I will make sure to put a summary at the top, or a quick link to the summary at the bottom.

Now I’m happy; as long as I provide an easily accessible summary I can continue to write at length for those folks here who want to know “everything”, yipee! 🙂

A superb article. I’ve never read anything so good in the popular media. The BrinkZone is a treasure.

Have you any comment on the research of your countryman Staffan Lindeberg, which implies that the diet in industrialized countries leads to serious problems?

Step 2 and especially Step 3 are of extreme interest to me, but since I can’t do anything about them, I’m perfectly happy to read all you write about Step 1!

I’d be particularly interested in your views of the work of the evolutionary biologist Michael Rose and his

coworkers, which leads to the suggestion that not only does aging stop but that the ago of its cessation can be brought forward radically. Also in Aubrey de Grey, although that may be more on Step 2 or even 3.

I am very glad to hear that 🙂

Yes, Dr Lindeberg, like Dr Cordain, have contributed a lot to our understanding of the paleolithic diet and how our modern lifestyles are misaligned with the requirements of our ancient genes. While there are certain aspects of the paleolithic diet that I don’t agree with (especially their restriction of dairy and salt) overall I think the paleolithic diet can provide a good nutritional base and guideline for the affluent obese population, and those suffering from chronic diseases.

Like you, I am very interested in the step 2 and 3. What we can do now is to apply the knowledge and implement as much as we can of step 1 to our lives, so that we live until step 2 and 3 become common practice 🙂

Very nice, thoughtful piece, Monica. And, thanks, Will, for giving this topic a platform.

I am looking forward to Part II.

Glad you enjoyed it. Monica passed the Will Brink/BrinkZone “smell test” easily (which so few do…) so I had to have her here as a regular writer. 🙂

My great pleasure 🙂

Awesome topics, amazing writing capabilitie and a body to let us know that you walk the walk..

Thanks Kathleen 🙂

Pardon me for appearing negative here and I don’t want this to be construed as a personal attack, but my comments are critical, just to be up-front. First, my background: I’m 60 years old, have trained with weights and done cardio training for the last 45 years. I competed in contact sports in both high school and college (football and wrestling) and was a powerlifter in both high school and college, as well. In addition, I’ve had sleep apnea since early childhood (yes, I’ve been on a C-Pap machine for over 10 years), which runs through the paternal side of my family. When you put enormous stresses like those on a human body, along with injuries and surgeries on top of one another you’re going to accelerate the aging process, plain and simple. I also have the feet of a 90-year-old, which just adds to the problems. Of course, I’ve left out a number of details which explain even more about my situation, but I don’t want to bore everybody. I will, however, answer any questions, if necessary. Now that I’ve given some background, here’s where I view the above article with a somewhat jaundiced, skeptical eye: I’ve always found it difficult to accept the findings on the aging process from someone who isn’t even CLOSE to being middle-aged. Monica’s educational credentials are impressive, but after being around bodybuilders for many years, I find it hard to believe she achieved that level of muscular development without the aid of some kind of anabolic or HGH substance, at some point in her training life. Knowing the psyches of some bodybuilders when it comes to their self-image and justification for drug use, I always find it difficult to accept what they say. Obviously, Monica has supplied a lot of data to back up her observations and I applaud her for that. My assertion is, until you’ve studied someone like me, who didn’t get the genetic gifts, who put in a lifetime at various gyms and who went through all the reconstructive and corrective surgeries, you don’t really have an idea of what it’s like to go the aging process. I would much rather read an article from someone who is in my age group, who has paid their dues like I have and doesn’t have a young bodybuilder’s mindset. I’m in no way denigrating Monica’s credentials or her physical appearance, nor is this any kind of a personal attack, as I mentioned before. Like everyone, I have an opinion, right or wrong.

Sorry, I left out the word “through”, in the sentence, “through the aging process”.

Oh, dear. Were 87 references not enough for you?

I found Monica’s piece to be straightforward and without bias. Surely her discussion of allostatic load references the wear and tear you have experienced.

I am in your age group. But I do not share your opinion that (1) a person much younger than us cannot write a significant piece about aging, and (2) someone with Monica’s physique has no right to discuss this issue.

In fact, I surmise that if Monica’s photos were not included, you would not have commented in the manner that you did. What should a person look like to win your respect? Old and battered?

LOL, I can do middle aged and battered pretty good! 🙂

I’m the poster boy!

You’re blowing my comments way out of proportion, nor did you read it carefully enough to know I prefaced my remarks by saying I wasn’t making it an attack piece. In addition, I commented positively on the data Monica supplied. I never said she, or any young person for that matter, had “no right” to comment on aging, just that I view their comments with a skeptical eye, because they haven’t experienced anything close to what I have. Their outlook tends to be focused on their own, current state-of-being and, because experience is the best teacher, they can’t possibly understand what people like me have to go through on a daily basis. You are correct about one thing: if Monica’s bodybuilding photo hadn’t appeared, I might have viewed the article in a more favorable light. My experience in observing competitive bodybuilding over the last 30 years led me to the conclusion that it’s one of the toughest sports to compete in and also the unhealthiest. Would an old and battered photo of someone make me believe them more? Maybe. At least I’d know they paid the same dues I did and have taken some steps I’m not aware of to mitigate the problems they experience. But, there again, you’ve taken something out of context and blew it up to something it isn’t and over-dramatized it, as well. However, I’m glad you shared your opinion with me and I’ll give your comments some thought.

Kent, please note that I have never competed in bodybuilding. Why? Because I am not willing to sacrifice my health for a medal!

I applaud you for that. You could win contests, for sure, but your health might suffer. I’m rethinking my positions and comments. The back-and-forth is healthy. If you’ve never used anabolics, as well, you have my respect. It looks as if I shot from-the-hip, originally, but your and others’ replies have been interesting. Apparently, I have grossly misjudged you. I send out my apology and a “thank you” for clearing up my misconceptions.

Sigh. It was difficult but I did in fact read every word (and every backhanded compliment to Monica).

And my reply to you was barely enough to “blow your comments out of proportion,” Kent. There’s just one person here who’s been overdramatizing:

“Their outlook tends to be focused on their own, current state-of-being and, because experience is the best teacher, they can’t possibly understand what people like me have to go through on a daily basis.”

Oh, goodness. No more comments.

“You’re blowing my comments way out of proportion, nor did you read it carefully enough to know I prefaced my remarks by saying I wasn’t making it an attack piece. ”

I didn’t take anything out of proportion or context, I simply made it clear I didn’t agree with your comments.

” I view their comments with a skeptical eye, because they haven’t experienced anything close to what I have.”

As do I, but I also explained why that should not be the case here. You can take it as you wish, that’s fine. You offered an opinion, I offered a counter/differing opinion.

” Their outlook tends to be focused on their own, current state-of-being and, because experience is the best teacher, they can’t possibly understand what people like me have to go through on a daily basis. ”

And again, if they are giving advice based on their personal experiences, I agree 100%. I don’t generally take advice from kids who have not been there done that, unless they do it as she did: support it with the data, and not be preachy about it. Little I dislike more then kids telling me how to eat or train based on their 20+ years of life 🙂

“You are correct about one thing: if Monica’s bodybuilding photo hadn’t appeared, I might have viewed the article in a more favorable light.”

Then that’s your personal bias and mistake. It simple depends on *what* she’s writing about and how she does it. Two, women built like that and pretty are not supposed to be that smart in our culture, and be it unconscious or conscious, people have bias built into their perceptions. Back in the day, when i was approx 30lb heavier and leaner, I had a fake pair of round nerdy glasses made for seminars and such to get people to take me seriously. Worked like a charm…

“My experience in observing competitive bodybuilding over the last 30 years led me to the conclusion that it’s one of the toughest sports to compete in and also the unhealthiest.”

Competitive sports has nothing to do with health period. Sooner people realize that, better off they are. Ex pro football players, boxers, power lifters, gymnasts, etc, are often virtually crippled by the time they are in their 40s. The bodybuilding lifestyle is very healthy, high level competitive bodybuilding is not, and that applies to many sports.

” you’ve taken something out of context and blew it up to something it isn’t and over-dramatized it, as well. ”

Your opinion. I don’t agree, and neither, it appears, did others who read your comments.

“However, I’m glad you shared your opinion with me and I’ll give your comments some thought.”

Sounds like a plan 🙂

This has been very good and educational, for me. Thanks to all of you who replied.

Kent,

Apparently you believe that any athletic and physiological success is solely due to anabolics. Let me make it clear to you if that was the case, we would have way more athletic superstars around. Just taking anabolics and not eating or training properly, and having destructive lifestyles, will take you nowhere, as can be manifested by all the wannabes we can see in the gyms.

And FYI, my life hasn’t been easy either: I survived a very serious and traumatic brain surgery in my early 20s (I am now 31 years) that hospitalized me for 2 months!!! That experience certainly made me realize how delicate life is and impelled me to start study health promotion, not only to take care of my health but also to help others do that as well.

Let me give you a piece of advice: NEVER JUDGE A BOOK BY ITS COVER!

AMEN

Yes, I agree, we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. Lord knows, I’ve had it happen to me. However, I’ve observed competitive bodybuilding and bodybuilders for some 30 years and heard every excuse in the book for their drug use, therefore I tend to be skeptical about the things they tell me. The same reasoning has been true in Major League Baseball and the National Football League, despite the fact that they’ve taken steps, too late in my opinion, to curb or stop their use. I’m also fully aware that anabolic “help” alone won’t make one look like a bodybuilder (I’ve been around this for 45 years, in gyms of all kinds), that it takes a tremendous amount of work in both the gym and the “training table”. If you haven’t ever taken any anabolic substances, I applaud you. Once again, my observations have been that your kind of muscular development has been “helped”, at some point, by these chemicals. If you are the exception to that rule, you have my respect.

I’m almost twice your age, so I have the benefit of experience. You can’t possibly relate to what I go through, and that’s normal. However, as Will has commented, your article is a research piece, backed up by data. I have some skepticism based on personal experiences and that may be unfair, as I think about it, further. Your comments are well-taken by me, nonetheless, and I’ll digest them further.

Kent, thank you very much for that. Apology accepted.

Peace

Monica supplied, in great details, the general theories on what causes aging, not her personal opinions on aging. Thus, her age in that respect is irrelevant here. Had she claimed her experience eat X or doing Y exercise reduced the aging process, I might agree with your position, but I do not, and I have spent my fair share in the trenches, dealt with illness, am middle age, etc.

Two Monica’s personal appearance, also 100% irrelevant here. Again, if she was giving exercise/diet advice based on her personal experiences only as some genetically gifted kid, that’s another issue, but she’s not.

Thus, her well researched and objective article should be taken as a stand alone article, and a damn good one at that.

If I had prostate cancer, say, I might have some interest in talking to someone who had gone through it himself, but I would be incomparably more interested in finding the most highly-regarded specialist on the disease, and whether or not he’d had cancer himself would be of zero importance to me. The same with aging.

This argument makes me think of something we often hear in politics: some politician says “my opponent cannot represent the XXXXXX people, can’t understand their problems, because he isn’t one himself” where XXXXXX stands for whatever group – demographic, economic, whatever – the pol is trying to appeal to. Most people will reject this demagoguery; no politician can be a member of every group, and we try to elect political leaders who will study their dossiers, consult with their advisers, do their best to familiarize themselves with everyone’s problems.

Yes, Will, you’re right, and I made my comments based on personal experiences over the last 25 to 30 years. I probably misinterpreted things, based on Monica’s photo, which jaded my viewpoint. This article is data-driven, but I had skepticism about the messenger. If that’s unfair, then I apologize and I’ll back off those comments. I knew, however, ahead of time, if I left them, I’d get a strong response back. And, please, let me be clear, so we don’t have any misunderstandings, I’m in no way jealous or envious of anyone’s athletic success. I’m way beyond that kind of thing at this stage of life. Let me restate what I said, earlier, like everyone, I have an opinion, right or wrong. And, if I’m wrong, I have to admit that.

Informative and well researched article. Looking forward to part.

Great article Monica. As a baby boomer pushing the big 60, I have been working out for about 30 years in a variety of disciplines. Not only has it kept me engaged in life in a physically active and social sense, but it has helped me overcome a traumatic back and spinal cord injury as well mental duress caused by extreme personal loss. I view a lifestyle of continued learning about nutrition and physical activity imperative to anyone wanting to live a rewarding life, especially in one’s later years. A conditioned mind and body will help you get through the tough times as well as let you thoroughly enjoy the good times. Keep spreading the word. Cheers. FZ

Frank, thank you for sharing your experience with us. It is always nice to hear true real life stories, proving that successful aging is possible to accomplish.

Hi Monica,

Kudos for the article. There’s some significant research there. I agree with the earlier post, a summary of ‘do’s and don’ts’ at some point would be good.

I would also like to make one point. At risk of re-opening Kent’s can of worms I was surprised that hormones were not mentioned at all in your piece. This comment is not motivated by any judgment of this forum or of you, but considering the topic of the article this seems to be one glaring omission. Hormone replacement therapy is a very common intervention for those suffering the ‘symptoms’ of aging. And of course I am not only talking about women here. My understanding is that testosterone therapy is gaining credibility (and use). Why were these potentially useful features not discussed?

And just a side point for Kathleen. Don’t fall into the trap of assuming that a reference lends credibility to a point. As an active scientist myself, I know all too well how much dodgy science is out there in the published literature. Only once you invest the significant time required to individually assess the data, can you make any judgment on the validity of a paper’s claims. Skepticism should not stop at ‘science’.

I’m interested in your feedback.

Best wishes

Mike Tatham

Mike, if you do a search on “HRT” in the site search box, you’ll find where I cover the topic in various articles. Monica’s position on HRT and mine may differ however, so what you find will be my position/comments on the issue only. 🙂

Cheers Will. I’ve had a look and learned some new stuff. I’m a bit worried that training without T supplementation can decrease HDL levels though!

Mike

Thanks, Mike. I understand your point entirely. In fact, I just got into a “discussion” on another site about how you can’t always trust the study findings for any number of reasons.

Mike, thanks for the feedback.

The main purpose with this article is to introduce the concept of aging and its definitions and causes. Except in the section “It is never too late” I didn’t go into any specific anti-aging interventions because my intention is to cover that in part 2 (both dietary supplements and HRT, where I share Will’s position), which I will probably have to further split in several parts in order to avoid information overload.

Regarding references, I totally agree. There are degrees if quality in scientific data, as there are in other things. A solid reference should have been published in a peer-review journal. Unfortunately that’s not always the case. To make things worse, many scientists only cite supporting data for their own hypotheses, and then there’s always the issue of publication bias. That’s why every conclusion and supporting data should be viewed thru the magnifying glass of a skeptical detective. Mike, thanks for bringing this to the attention of our readers 🙂

I’ll look forward to part 2 then. Cheers Monica.

Mike

Hey Monica!

Great article!

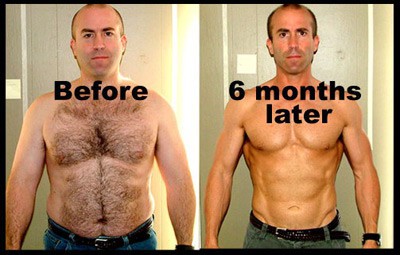

I just wanted to ask if this is really possible to lose that much weight like on the picture (before/later) within 6 months?? And what to do specifically to get in shape like that guy!

Greetings

Guido 🙂

I’m glad you like the article 🙂

That obviously depends on many factors. The purpose of the photo is to show what’s possible to achieve with proper diet and nutrition. Whether it takes 6 month or 12 months or more is not relevant here.

Monica,

Great artice!

What are your preferred brands of Whey, creatine and Omega 3 supplements?

jim

Monica,

Thank you – great article. Especially liked the age span section. I follow Original Strength Systems stuff and Tim Anderson, just wrote a piece on living to be 120 years old last week. His article was from a more biblical stance but incorporated the need for movement in staying “young”.

I’d say physical activity is the best anti-aging tool we have today.

One theory on aging that’s fascinating to me was presented by the late Dr John Yiamouyiannis, in “Fluoride, the Aging Factor”, a profoundly well-evidenced argument against adding fluoride to municipal water sources. Dr Y believed that the naturally-occurring fluoride in the earth’s crust, leaching into the water & air, was an unavoidable factor in our inescapable mortality. I think it’s at least as good a theory as anything else so far.

When it comes to health, disease and aging, there is no one single cause.

Each of the myriad theories on again may cover one particular aspect of aging; the new better multi-level theories encompass more than just one single cause.

Very good article.

Thank you. 🙂

I’ve come late to this article but found it very interesting. I am on the advisory group of an interdisciplinary study of frailty at the University of Manchester, UK (Frailty, Resilience and Inequality in Later Life) it has made me personally aware (I am aged 67) of the need for a good diet (I have now come down to 150 lbs) and exercise as I approach the danger years for frailty. I swim 2km daily and follow it with resistance training and a undenatured Whey Protein Isolate drink. I am now free of any symptoms of Ulcerative Colitis which I was diagnosed with about 10 years ago. Another complication is that I had polio as a child and that has left me with significant muscle loss in my right leg.

Anyway, the point I want to make is whether you have any advice for disabled older people and exercise. Also exercise and gym training can be a lonely business, are there any models of groups of older people getting together to share knowledge and provide mutual encouragement. I would certainly like to start a group up here (Manchester, UK)

many thanks

Bernard