Knee problems of varying descriptions are as common as five pound plates in gyms and health clubs throughout the world. Anyone who has recently experienced knee surgery will attest to their awareness of this fact, as they quickly begin to notice legions of zipper-like knee scars among their gymgoing peers.

The prevalence of these cases can be attributed largely to the fact that the knee is an anatomical vortex of sorts, where the body’s largest and strongest muscle groups converge upon the tiny, yet in most cases hardy, kneecap. Add to this a lack of basic anatomical knowledge, improper exercise technique and/or selection, and unsuitable workout gear, and the prescription for disaster becomes compounded exponentially.

In this discussion we will examine several factors which collectively, have the potential of determining your predisposition for experiencing knee symptoms. Much of this information has received minimal exposure from industry magazines and trade journals in the past, and therefore should be of considerable interest to current and prospective fitness professionals and health care specialists.

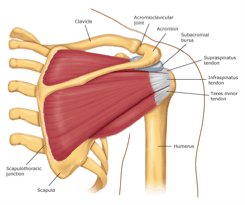

Knee Anatomy and Biomechanics

Keeping your knees healthy and asymptomatic begins with developing a functional understanding of how this unique joint is constructed (anatomy) and how it does and doesn’t function (biomechanics). The knee is relatively simple to understand from a mechanical perspective, but please refer to the appropriate illustrations as you read this section— doing so will enhance your comprehension of the discussion.

The knee is an unarthroidal (meaning movement in one direction only) hingetype joint, roughly equivalent to a door hinge for practical purposes. Five different types of structures are involved in the knee’s functional anatomy— bones, ligaments, tendons, muscles, and articular cartilage. Here then, is a brief definition of these structures:

Bone: Purposeful human movement would not be possible without bones. The four bony structures which are involved in knee function are the femur, or thigh bone, the tibea and fibula (the shin bones), and of course, the patella, or kneecap.

Ligaments: Fibrous and very tough connective tissue which connects bone to bone, providing stability and integrity to the joint. Two sets of ligaments help to stabilize the knee joint— the anterior and posterior cruxiates, which are deeply located within the knee, and serve to limit rotation and hyper-extension, and the co-laterals, one on either side of the knee. The co-laterals protect the knee from being moved from side to side, and help to establish the integrity of the joint by keeping the tibea and femur attached to one another.

Tendons: Fibrous bands that that connect muscles to their bony attachments. In the knee, the patellar tendon connects the quadriceps muscles to the patella, and then in turn to the upper shin.

Muscle: We all have a clear idea as to what muscles are, but let’s examine the ones that cross (via their tendinous attachments) the knee joint. First are the quadriceps, the powerful muscles of the anterior (front) thigh. Next are the hamstrings, or the leg biceps, located on the posterior thigh. Finally, the gastrocnemious, the most superficial calf muscle, crosses behind the knee joint, where it contributes as a knee flexor.

Articular Cartilage: You’ve heard of “torn cartilage” in knee injuries before. cartilage is the connective tissue which provides for a smooth articulation between bones at the joint. Cartilage also acts as a shock absorber. The meniscus is the knee’s only cartilage. Located on the tibeal plateau, it cradles the femoral condyle, or the rounded knobs of the lower femur. Since the tibeal plateau is flat, and the femoral condyle is rounded, the meniscus provides a better “fit” between these two structures.

Training Gear For Healthy Knees

For most, training attire is primarily a matter of vanity— looking good while you’re training. But two pieces of standard training gear— your shoes and knee wraps— should be carefully selected and applied, not only to maximize comfort and short term safety, but more importantly, to ensure the long term health of your knees.

Your shoes are literally where the rubber hits the road. We urge you to think of your shoes as the foundation of your leg training sessions. Wearing old or broken down fitness shoes for heavy squatting or leg pressing is like putting old, worn-out tires on a race car! There are several reasons to avoid training in your “tennies:”

First, most general purpose fitness shoes simply lack adequate stability, and have little or no arch support for heavy lifting. As you squat, your feet may develop a tendency to pronate, or “cave in” toward the inner side. When this happens, the knees are also forced inward, leading to a constant strain on the medial collateral ligament, excessive shear force on the meniscus, and improper patellar tracking, which in turn can lead to chondromalacia (to be discussed shortly).

If your feet tend to pronate anyway, or if you’re prone to being “knock knee’d” (and these two conditions are very often associated with one another), it becomes even more important to select good training shoes. Another important reason for using specialized shoes for squatting or other heavy leg training movements is that they provide a deep and solid heel cup, which prevents the foot from rocking and rolling laterally (to the outside) when it is compressed under heavy loads.

Finally, there is a difference between a shoe being worn out and being broken down. Even if your shoes look fine, they still may offer no arch or heel support at all, either because they never had any to start with, or because after a handful of heavy leg sessions, the supports have compressed to the point to where they no longer function as they were intended. Think about it— a tennis shoe is meant to support a 160 pound tennis player, NOT a 600 pound leg press! Loads like these cause the shoe to break down without visual signs of wearing out.

We strongly recommend that you choose a heavy-duty training shoe (please see corresponding list of companies that offer these shoes) that you use for training, and training only. Use a stable running shoe or cross trainer for everything else.

Knee wraps have long been a mainstay for competitive powerlifters, and for good reason. When properly used, wraps can dramatically improve knee safety during heavy squatting and leg training sessions. Whenever you contract your quadriceps muscles, the patellar ligament “wants” to pull away from it’s attachment at the upper front aspect of the tibea. During squatting, for example, the heavier you go, the lower you go, and the faster you descend, the more this tendency is compounded. Please refer to the sidebar below on proper knee wrapping.

You’ll notice that the wrap is tightly wound in a cylindrical fashion around the upper shin (where the patellar ligament attaches), then more loosely wound over the kneecap itself (this is important to avoid grinding the patella into the femoral condyle, creating a case of chondromalacia for yourself), then tightly wound over the lower third of the thigh. The rationale for wrapping the knees prior to heavy squatting is that it reduced the pulling forces on the patellar ligament at it’s attachment to the shin. This translates to significantly reduced chances of avulsing (detaching) your patellar ligament during heavy leg movements.

According to Dr. Paul Ward, knee wraps also provide several other benefits beyond protection of the attachment site of the patellar ligament. These benefits include keeping the knees warm, which improves blood flow and tissue elasticity, reducing the possibility of muscle tears during high-intensity leg pressing or squatting. Additionally, knee wraps assist the patella in tracking normally over the femoral condyle, reducing the possibility of developing chondromalacia.

Stance Variables Affecting Knee Health

Whenever you squat, hack squat, or leg press, your foot position is an important variable in determining not only the results you’ll obtain from the exercise, but also the safety of your knee joints. Although each individual must determine their own best stance exercise per exercise (based on their own anatomical peculiarities such as height and leg length), the following variables must be taken into consideration:

1) The quadriceps muscles can contract more efficiently when the feet are pointing slightly (about 25 to 30 degrees) outward as opposed to straight ahead. If you squat with a very wide stance, your adductors tend to assist the quads. This can result in stress to the medial collateral ligament, abnormal cartilage loading, and improper patellar tracking.

2) During the decent phase of any type of squat, do not allow the knees to move more than 2-3 inches forward of their locked position. The further your knees travel over your feet, the greater the shearing forces on the patellar tendon and ligament. To avoid this, descend into the squat as if you were sitting back and down into a chair. Don’t worry if you lean forward a bit as long as you maintain a tight and arched back, and keep your bodyweight over the center of your feet. The ultimate objective is to keep the shins as vertical as possible throughout the entire movement.

3) In any leg training movement, make sure that your knees are tracking directly over your feet, not to the inside or outside. Many lifters turn their knees inward during the concentric phase of a heavy squat, and they usually aren’t aware of it. Give your clients immediate feedback, since after all, they shouldn’t be looking at their feet during the lift! If a client turns the knees inward, insist that they back off on weight until more correct movement patterns are mastered. Consider videotaping the squat session to provide unquestionable evidence when needed.

4) During the concentric portion of squatting or leg pressing of any kind, instruct your clients to “push from the heels.” This not only enforces a vertical plane of the shins, but also allows the quads to contract with maximum efficiency. Balance will improve as well, which adds an extra margin of safety.

5) Although many top bodybuilders advocate a very close stance for the purpose of “isolating the quads,” when squatting, remember the inherent tradeoffs in all ergogenic (work-enhancing) techniques. In this case, any leg training technique that isolates the quads also intensifies the shearing forces to the patellar tendon and ligament. A lucky few have knees that can take this type of punishment, but for most of us, a slightly wider stance, with toes pointing slightly outward and shins vertical, is a much safer and still very effective alternative.

6) Finally, teach your clients to be efficient in the exit out of the rack, and getting “set” in the squat stance. After lifting the weight off of the pins, the lifter should take just one step backward as immediately assume the squatting stance. This takes time to master, but eventually all the minute adjustments can be pared down substantially. Once set in the stance, cue your clients to keep their feet “nailed down” for the duration of the set. Many people “fidget” with their feet and toes between reps which can cause a variety of problems ranging from a break in concentration to a loss of balance.

How to Use the Knee Wraps

Knee wraps are only effective if used properly. So, if you’ve never used them before, take a moment to read this:

Sit on a chair or bench. Begin with the wrap completely rolled up (this makes the process much easier than fighting with a six foot tangle of cloth). With your leg straight, start applying the wrap on the upper portion of your shin. Wrapping from “in” to “out,” (counterclockwise for the left leg, clockwise for the right), anchor the wrap by applying 2-3 layers on the upper shin, then move upward, overlapping each previous layer by one-half the width of the wrap. When wrapping around the patella, make sure the wrap is a bit loose to avoid excessive pressure on the kneecap. Apply the wrap tightly again as you move past the knee, stopping somewhere on the lower third of the thigh. Tuck the end of the wrap under the previous layer to secure it. Repeat for the other leg.

Common Problems of the Knee

Chondromalacia: Degenerative changes (roughening) of the underside of the kneecap. Causes pain when rising out of a chair or when climbing stairs. Think about getting a grain of sand under your eyelid— the synovial fluid acts the same way! Tight quads are responsible for 80% of chondromalacia. Other causes include repetitive overuse, genu valgum (“knock-knees”), and a shallow lateral femoral condyle.

Some very thorough points about the squat here Charles, I’ve been squatting for a long time since I was about 15 and I can fortunately say that I have never had a bad knee injury (touch wood!), I really do think that squatting makes all the knee region a lot more secure and stable. Interesting point about the exit out of the rack too, I never considered that.

I have not used wraps in years, but perhaps I will add it back into my program.

Wraps tare recommended at 300 pound and up for a squat. if you have chondromalacia (noisy knees) and no associated pain it is not a problem according to everything I have read.

Never ever used wraps.

Some people recommend Chuck Taylor for squating since they are very flat. What is your opinion on that?

I have recently diagnosed osteoarthritis in both knees. Are you aware of exercises/exercise regimes/resources that would most benefit someone with my situation?

Thanks.

Yeah, like Loni, I would also like to see the list of companies who carry these shoes, and the info on the wrapping. Thanks.